Dear Censor,

Wait a moment before you tear out these pages. Aren’t you at least curious about this new Mao biography and why it’s been banned from China, along with any material discussing it? The Americans’ War on Terror seems to have grown passé; the pressing questions seem to be Whither China? and How will the United States respond? In fact, a series of top-shelf foreign policy venues devoted significant space to this very topic this past fall. Writing in The American Interest, neo-conservative guru Francis Fukuyama proposed a new containment policy modelled on America’s Cold War approach. In The National Interest David M. Lampton, on the other hand, advocated “hedged integration,” gradually bringing China into “an interdependent international system in which it hopefully will develop shared responsibility for system maintenance.” It’s obvious that the Americans, and Westerners in general, are thinking a lot about your country these days. But with your nation enjoying billions in global trade, basking in America’s long-delayed recognition of its might, and preparing to host the 2008 Olympics, an 800-page gorilla shows up to ruin, well, the party. Dear Censor, Wait a moment before you tear out these pages. Aren’t you at least curious about this new Mao biography and why it’s been banned from China, along with any material discussing it? The Americans’ War on Terror seems to have grown passé; the pressing questions seem to be Whither China? and How will the United States respond? In fact, a series of top-shelf foreign policy venues devoted significant space to this very topic this past fall. Writing in The American Interest, neo-conservative guru Francis Fukuyama proposed a new containment policy modelled on America’s Cold War approach. In The National Interest David M. Lampton, on the other hand, advocated “hedged integration,” gradually bringing China into “an interdependent international system in which it hopefully will develop shared responsibility for system maintenance.” It’s obvious that the Americans, and Westerners in general, are thinking a lot about your country these days. But with your nation enjoying billions in global trade, basking in America’s long-delayed recognition of its might, and preparing to host the 2008 Olympics, an 800-page gorilla shows up to ruin, well, the party.

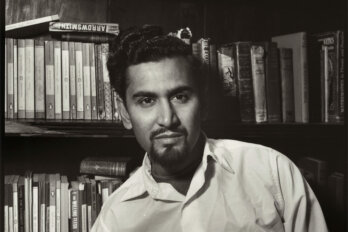

Jung Chang came to international prominence in 1991 with her enraged and personal account of women’s lives in twentieth-century China. Wild Swans sold in the millions and led authorities to ban the book. Chang’s new work, a sprawling biography of Mao Zedong (Tse-Tung) entitled Mao: The Unknown Story, written in collaboration with her husband, Jon Halliday, will not win over her antagonists in the Politburo. Researched and written over the course of nearly two decades, Chang and Halliday’s governing premise is simple and wholly damning: Mao Zedong was a calculating thug of titanic proportions, obsessed with gaining total power in China and beyond, at any cost, and by whatever means were necessary. The Great Helmsman’s achievements were born of a near-reptilian view of his fellow man and a tyrannical disregard for the value of any human life save his own. Mao makes Stalin and Hitler look like mediocre tyrants, as Chang and Halliday’s opening statement suggests with characteristic bluntness: “Mao Tse-Tung, who for decades held absolute power over the lives of one-quarter of the world’s population, was responsible for well over 70 million deaths in peacetime, more than any other twentieth-century leader.”

Born to peasant stock in Hunan province in 1893, Mao took a middling road to national greatness. He seems to have never progressed beyond the slouchy habits of a wayward teenager. Throughout his life, Mao was fickle, lazy, and lecherous, prone to petty chicanery, and congenitally self-involved. He first converted these adolescent vices into political virtues when he joined and then bashed his way through the ranks of the Chinese Communist Party. From the beginning of his party involvement in the early 1920s, the authors suggest, Mao viewed the possibility of a Chinese proletarian revolution only as the means to a higher end — personal advancement. He had no abiding commitments to Marxism or to the ccp, nor did he display intellectual tendencies of note, unless one counts a lifelong habit of writing bad poetry. Nor, for that matter, did Mao possess any leadership skills — eloquence, bravery, self-sacrifice — that might account for his sway over so many. Mao’s talents lay in exploitation, manipulation, and spreading terror; he capitalized on cohorts’ loyalties and fervour by encouraging wide mistrust, blind obedience, and vicious behaviour. He was also adept at manoeuvring the ccp’s rigid command structures and bureaucratic armature to entrench his position, often relying on hacks to do the necessary dirty work and then distancing himself from the outcomes through exiles, torture, and executions.

The first half of Chang and Halliday’s biography details Mao’s inglorious ascent and sets out the contours of his future tyranny. It involves an account of how Mao outflanked competitors by currying favour with the Soviets — they found his talent for brutality pleasing and it allowed them to tolerate his persistent insubordination. The authors describe how he built himself an army by hijacking colleagues’ troops only to waste the men in pointless campaigns; of how he did away with challengers and their families with indifferent equanimity; and of how a combination of inept Nationalist leadership and a great deal of Soviet money and meddling eventually brought him total power.

In the lead-up to Communist victory in 1949, the founding of the first Chinese Red State in Jiangxi province and the circumstances of the Long March encapsulate the systematic madness that would come to define Mao’s rule. In late 1930, Mao wanted to reassert his authority over the Red Army base in Jiangxi. Initially stymied, he claimed that wealthy peasants were in control of both the local party and the base’s troops, and he persuaded party leaders in Shanghai and Moscow to support actions he deemed necessary for maintaining ideological purity and full authority. In fact, he had already approved an array of sadistic tactics in order to extract confessions for these charges. Wives of Jiangxi leaders were singled out. According to one contemporary account, “their bodies, particularly their vaginas, were burned with flaming wicks, and their breasts were cut with small knives.” According to another report, male suspects would have a wire shoved through their penises; the other end was hooked around the ear of the victim, and the torturer then plucked at the wire.

In all, tens of thousands of people were eliminated in Jiangxi. Mao’s penchant for labelling opponents “counterrevolutionaries” as a pretext for their eradication started in earnest with the Jiangxi atrocities, Chang and Halliday contend, but the event holds wider historical importance: It was “the first large-scale purge in the party, and took place well before Stalin’s Great Purge.” When Mao was made chairman of the Red State in Jiangxi, in short order “a large square was cleared . . . to make room for the Communists’ staple activity: mass rallies.” Mandatory parades were held in the name of party greatness. In time party boss Zhou Enlai ran this Red fiefdom, “and under him the whole society was dragooned into an allencompassing, interlocking machine.”

The Long March is far better known than the carnage that occurred in the province of Jiangxi, which is why Chang and Halliday devote three chapters to debunking what they call “one of the biggest myths of the twentieth century.” Their aggressive narrative brings new material to light, but their handling of it leaves one wanting a more objective treatment. With Nationalist forces pummelling the Red Army in Jiangxi in October 1934, Mao took some 80,000 people on a year long, 9,000-kilometre trek to reach Communist territory in the north. In Chang and Halliday’s presentation, the Long March was a moving charnel house whose real purpose was to enable Mao to remain in command of his forces and eventually rise to the top of the party. Thanks to ill-conceived battles along the way and Mao’s purposefully dilatory navigation, not to mention mountainous terrain, harsh climate, and scarcity of food, some 70,000 died or deserted in transit. Beyond making a case for Mao’s culpability for the horrors of the Long March, Chang and Halliday indict two other men for ensuring its immediate success and later, mythic proportions: Chiang Kai-shek and American journalist Edgar Snow.

Once the Long March was underway, Chiang allegedly manoeuvred the Red Army into areas where its presence would rein in the activities of local warlords. He also avoided opportunities to decimate Mao’s forces himself because he was seeking to placate Russia and also deflect Japan’s imperial designs on Chinese territory. In defiance of official Nationalist and Communist histories, as well as most modern scholarly accounts, Chang and Halliday argue that “the famed Long March was to a large extent steered by Chiang Kai-shek.” Thanks largely to Chiang, soon after the march was completed Mao reached the top of the ccp. Enter the magnificently gullible Edgar Snow, who penned Red Star Over China, which is based on interviews with the chairman and other communist leaders conducted in 1936. After Mao rewrote segments to make them more to his liking, the book was published in 1937 and influenced both international and native opinions.

At the heart of Snow’s fable and Mao’s mythology, Chang and Halliday explain, is “the crossing of the bridge over the Dadu River,” which occurred halfway through the Long March. The authors provide Snow’s breathless account of the Red Army making its way across a partially disassembled (and then a burning) bridge while facing enemy machine guns. Then they offer a curt dismissal of on Snow’s rendering: “This is complete invention.” To dispute the unblinkingly heroic version of the event, Chang and Halliday cite the testimony of a ninety-three-year-old local witness they interviewed in 1997. They combine her recollections with other piecemeal evidence, but only to produce a counter-history of the Dadu crossing as vehemently negative as the Snow/ccp version was positive. Here as throughout the biography, Chang and Halliday advance their iconoclastic attack on Mao by relying on source materials that resist independent verification, and through historical recreations that depend on questionable logic. But the force of Chang and Halliday’s chief argument — that an outsized egoist held a nation captive to his monomania and concealed it through a combination of saturating ideology and idolatry — counsels against the ready acceptance of a monolithic story, whether of good or evil.

The second half of Mao: The Unknown Story details Mao’s implacable appetite for power and creature comforts once the Communists had taken over China from the Nationalists. Having already gained decisive control of the ccp, from his ascent to power in 1949 until his death in 1976 “Mao would digest the rest of society gradually.” The trajectory is depressingly similar to the account of Mao’s rise, and even more troubling in that the three main features of Mao’s leadership — obsessive control, opaque decision-making, and aggressive expansion — describe the contemporary Chinese approach to governance just as readily. Among the numerous topics covered in grisly detail are Mao’s jockeying for support and position with Stalin and his Soviet successors; the brutal ironies of his Hundred Flowers campaign; his obsession with nuclear weaponry; the Great Leap Forward from 1958 to 1960 and its major achievement, widespread famine; the rise of the Little Red Book and the personality cult; his compulsion to best the United States; the countless and self-defeating purges that he presided over to hold on to power; his constant recalibrations of his cronies’ positions, responsibilities, and influences; his proto-Taliban approach to his nation’s cultural heritage; China’s military involvements across east and south Asia; and, climactically, the Cultural Revolution in all its horrific absurdity.

In addition to the public dimensions of Mao’s rule, Chang and Halliday catalogue his myriad imperial habits and private vices. Deluxe bunkers were built throughout the country based on the often unmet possibility that the chairman might visit; national railway schedules were overturned whenever Mao felt like travelling; and any number of functionaries and ordinary citizens had to abandon their families, practice abstinence, and take up faraway posts at the chairman’s bidding. Meanwhile, Mao officially plumped his self-image as “Serving the People” even as he enjoyed orgies at his villas, had his rice grains individually husked, and maintained a bulging bank account that let him play at noblesse oblige.

By the early 1970s, Mao’s health was deteriorating rapidly, and he was aware that he had a tenuous hold on power in the gory wake of the Cultural Revolution. And so, he looked beyond China for acclaim and validation. Most famously, he brought Richard Nixon calling in 1972. In Chang and Halliday’s scathing recreation of their meeting, the Chairman easily manipulated the unctuous US president into a neutered but widely followed summit that confirmed China’s superpower status. After this visit Beijing received wide diplomatic recognition, while the beaming, blacktoothed Chairman became “not merely a credible international figure, but one with incomparable allure.” With open distaste, Chang and Halliday note that, “World statesmen beat a path to his door. A meeting with Mao was, and sometimes still is, regarded as the highlight of many a career and life.”

Among the Western leaders whom this biography reveals to be dupes is Pierre Elliott Trudeau. Chang and Halliday briskly dismiss Two Innocents in China, the travelogue he co-wrote with Jacques Hébert based on their experiences in China in 1960, as “a starry-eyed book” because it ignored reports of famine the same year some twenty-two million died of starvation. Trudeau’s account of his post-Nixon meeting with Mao in his 1993 Memoirs is a gushing embarrassment unto itself:

I have vivid memories of meeting this former revolutionary, the son of a peasant, who now headed these vast armies of people. When I went back in 1973, I didn’t ask to see Mao, but my delegation rather hoped — and, to be honest, so did I — that I would have the opportunity. Would the Great Helmsman be in good health while I was there, and would I be received? That was the big question . . .

Eventually, Trudeau explains, he is taken to meet “this venerable gentleman . . . [who was] looking like a sort of Buddha” and, he notes, “we sat down and had a long talk. He did most of the talking.” Whipped up into a frenzy of Marxist orientalism, Trudeau writes of his last encounter with Mao with the enthusiasm of an overgrown teenager meeting an aged rock star.

Mao: The Unknown Story goes a long way toward undermining the cult of personality that officially hovers around Mao, but unfortunately it merely replaces one cult with another, exchanging the deific for the satanic. In Chang and Halliday’s handling, Mao was a leviathan figure without precedent, responsible for basically all of China’s terror-filled modern experience. The authors neglect to consider how centuries of imperial rule in China prepared the ground for Mao, and they write out of open, righteous hostility to their subject. Moreover, they tend to downplay the fact that many Chinese participated in Maoist programs at various levels — willing enthusiasts, unfazed supporters, cons, and quietists — which the book’s photographic sections make distressingly clear. They argue that citizens committed inhuman acts against each other out of fear, and because their sole opportunities for improving their horrid lives required them to betray, ruin, or destroy others. These are persuasive explanations, but only to the degree that they are in keeping with Chang and Halliday’s victim’s justice approach to chronicling Mao’s life and times.

In fact, the unstinting vehemence of their biography makes an older book on Maoist China, Chinese Shadows, a welcome tonic. Written by Pierre Ryckmans in 1973 under the pseudonym Simon Leys, it provides a withering, dispassionate account of “how heavily Mao has weighed on China’s destiny, and how much his presence has become a paralyzing factor in the life of the country.” But rather than focusing exclusively on Mao, Ryckmans considers the stifled, despondent experiences of the ordinary citizens living under his regime. His findings, based on chilling evidence taken from his travels throughout China shortly after the Cultural Revolution, led the Belgian sinologist to note that “the Chinese tend to look at human behavior in terms of role-playing and to consider themselves somewhat as actors playing their own existence.”

With critical sympathy, Ryckmans offers a disconcerting explanation for why Mao’s rule was able to persist for so long, cause so much suffering, and elicit such widespread zeal. More so than Chang and Halliday, he recognizes at least some self-awareness and agency in ordinary citizens, even if these were put to dark ends out of fear, resentment, or detachment. While brooking no illusions about Mao and his regime, Chinese Shadows comes across as a wiser book than Chang and Halliday’s comprehensive but one-note biography, perhaps because its task is more demanding: to account for human tragedy under totalitarianism on an individual basis rather than to simply ascribe it to a monster and proceed to compile an inventory of his many evils.

Indeed, concentrating entirely on Mao’s wickedness, Chang and Halliday limit their work’s most vexing point to a bitter afterthought: “The current Communist regime declares itself to be Mao’s heir and fiercely perpetuates the myth of Mao.” Coming to terms with this regime, its dreadful genealogy, and its future movements, is a burdensome undertaking that Mao: The Unknown Story makes more demanding and necessary — for more than just a handful of American policy experts and their Washington audience. Risen China represents a difficult but unavoidable challenge for the wider international community and, perhaps most importantly, for the 1.3 billion people who remain part of its Maoist machinery.

Which brings us back to you, dear Censor. Do you remember the patriotic poems of the Cultural Revolution? One went “O Chairman Mao, you are the red, supremely red Red sun which shines in our hearts, We wish you a long life, a long life, a life without end!” Still feeling that enthusiastic? Perhaps all you can bring to mind from Mao’s time is his beatific face. After all, it hung in every home. One of the most popular of the Great Helmsman’s portraits was called “Chairman Mao Walks All Over China.” How’s that title strike you now? But I’ve kept you too long. You should probably get back to work. Tear away.