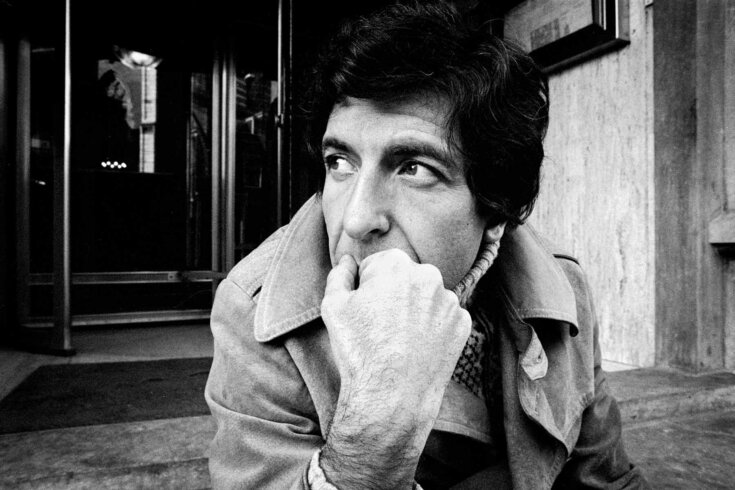

In the early ’70s, Leonard Cohen was in crisis. His life felt meaningless, although, in theory, it shouldn’t have. He’d spent the past decade doing all the things people were supposed to do in the ’60s. He’d joined shadowy religious orders and dabbled in Eastern mysticism. He’d written a sexy experimental novel that thrilled the young and enraged the establishment. He’d reinvented himself as a singer-songwriter and played to crowds of ecstatic flower children. He’d taken all the drugs, smoked all the cigarettes, slept in all the iconic hotels—the King Edward, the Chelsea, the Chateau Marmont. If the ’60s counterculture were a mountain, he was the rare mountaineer who’d made it to the summit.

And what had he found there? Not much, except rock and thin air. In the book Who by Fire (2022), journalist Matti Friedman tells the mostly unknown story of Cohen’s post-’60s funk and the series of events that brought him out of it. In 1973, Friedman explains, Cohen was living with his on-again-off-again girlfriend Suzanne Elrod and their son, Adam, on Hydra, a Greek island in the Aegean Sea. He spent his days in a fog of self-loathing. He hated the hippie scene. He hated poetry. He hated folk music. (“I just feel like I want to shut up,” he told a journalist from Melody Maker.) It wasn’t his first or last depressive episode, but it was surely one of the deepest.

Salvation, Friedman explains, came in an unlikely form. On October 6, 1973, 1,500 kilometres southeast of where Cohen was living, Egyptian troops began streaming eastward across the Sinai Desert, toward Israel, moving in tandem with Syrian forces, which invaded from the Golan Heights in the north. The attack was a surprise timed to coincide with Yom Kippur, the end of the Jewish new year—a day of fasting, prayer, and atonement. The Egyptian and Syrian armies were looking to recapture territory that Israel had annexed in 1967. But unlike that previous war, which the Jewish state won within six days, this one left Israeli troops inundated and fearful of defeat. On Hydra, Cohen caught the news from the Levant while toggling between radio stations. “I wanted to go fight and die,” he wrote. Then he boarded a plane to Tel Aviv.

Friedman devotes the rest of his book to the month that followed. Cohen found his way to the front lines of the war, where he served as an entertainer for the troops. The experience restored him. His previous visit to Israel, in 1972, had culminated in a near-disastrous concert in Jerusalem. He’d taken the stage, high on LSD, feeling jittery and unworthy. Who was he, he wondered—an effete Jew who’d abandoned religious orthodoxy for a hedonistic celebrity lifestyle—to perform in the Biblical city itself? What right did he even have to be there? He’d walked off stage halfway through the show. (The cheers from the crowd eventually brought him back on.)

But a year later, Cohen’s war experiences quickly put his earlier doubts to rest. He wasn’t a soldier, but he lived like one, sleeping on the ground and subsisting on combat rations. He played at airbases, field hospitals, and encampments—locations that were targets for enemy fire. He sang the same ballads he’d sung in Jerusalem a year earlier, but when he performed them now—in a moment of crisis, in the shadow of death—they took on a new urgency. Cohen, at last, seemed worthy of their power. Who could question his Jewishness now? Or his bravery? Or his masculinity? Who could deny that his songs had meaning? “I came to raise their spirits,” Cohen reportedly said of the soldiers, “and they raised mine.” After the war, he returned to Hydra reinvigorated, eager to have another child and record a new album.

Friedman’s book is fascinating not only because it offers a lost chapter in Cohen’s biography but also because it deepens our understanding of the Cohen persona. It’s hard to read the book and not feel the tug of reactionary ideas. The story, ultimately, is that of a liberal bohemian whose comfortable life in the West brings him to the brink of self-annihilation until (fortuitously) a war comes along, enabling him to heal his ailing psyche and restore his manly vigour. Cohen is brought low by fame, drugs, and Western decadence. The forces that revive him? Mortar fire, gallantry, martial struggles in a Biblical locale.

One sees overtones, here, of Ernst Jünger, the German philosopher who suggested that men experience life most vividly when toiling in the presence of death, or of Nicolás Gómez Dávila, the Colombian aphorist who declared that “modern man is a prisoner who thinks he is free because he refrains from touching the walls of his dungeon.” (When Cohen was at his lowest, he was an embodiment of Dávila’s modern man, imprisoned by freedom itself.) One also notices echoes of Michel Houellebecq, the misanthropic French writer whose novels depict a godless, hedonistic culture where humans live in a state of persistent low-grade misery.

One might bristle at a comparison between these writers and Cohen. We think of them as sinister reactionaries; we think of him as a fedora-clad sex symbol. But Cohen had a conservative streak too, although we rarely talk about it today. Reactionism was seldom his dominant mode, but it was often there, both complicating and complementing his humanism. You can’t wish it away. Nor should you want to.

A reactionary, to put it crudely, is a person who’s enthralled with the past. There are as many strands of reactionary thought as there are verses in the Bible, so it’s hard to say anything definitive about reactionism. But if you’ve ever fantasized about the days of yore—a bygone world of religious and dynastic traditions, military heroism, and close familial networks—then you can understand the appeal of reactionary thought.

It’s also hard to say how reactionism differs from conservativism. A popular definition holds that conservatives want to keep things as they are—they want to prevent change, or at least slow-walk it—whereas reactionaries want to return to the past. But in practice, reactionary and conservative ideas often blend together. Few people subscribe to one and not the other, and probably all people entertain both from time to time.

As it happens, I understood Cohen as a reactionary before I understood him as a liberal, mostly because of the random way I first encountered his work: as a teenager, watching Oliver Stone’s crime thriller Natural Born Killers, whose soundtrack features “The Future,” a track from Cohen’s 1992 album of the same name, in which reactionary ideas are most fully explored.

That song still colours my sense of what he was all about. It depicts a dystopian future in which modernity (“the blizzard of the world”) has “overturned the order of the soul.” People are alienated from love, from bodily pleasures, and from the rituals of prayer and atonement: “When they said ‘repent,’” Cohen sings, “I wonder what they meant.”

The speaker in the song is clearly a man in crisis. At times, he pines for a totalitarian leader or a rigid system of thought that can impose meaning on a meaningless world. “Give me back the Berlin Wall,” he sings. “Give me Stalin and St. Paul.” At other times, he resorts to thrill seeking to distract himself from the vacuousness of the present: “Give me crack and anal sex,” he declares. “Destroy the only tree that’s left / Stuff it up the hole in your culture.” In a meaningless world, Cohen implies, people become atomized and desperate, seeking escape in whatever pleasures they can find. (In his live shows, Cohen eventually replaced “anal sex” with “careless sex,” correcting for the homophobic or sex-negative overtones in the original lyrics.)

Cohen has said that “The Future” was inspired by the ’92 Los Angeles riots, in which parts of the city became ungovernable. But Cohen’s Los Angeles also resembles the ’60s-era California so famously depicted by the journalist Joan Didion—a world of brush fires, broken traditions, and criminality.

For Didion—a writer whose reactionary tendencies were well documented—there was one celebrity who exemplified the dark energy of the moment: the cult leader Charles Manson, who orchestrated the Tate-LaBianca crime spree in August 1969 that left seven people dead. Didion viewed the Manson family murders not as a change in the moral weather but rather as a storm that had long been brewing. When you abandon the rituals and folkways of the past, she argued, when you replace scripture with rock ’n’ roll and supplication with LSD, you don’t get utopia: you get entropy. The hedonism and permissiveness of the ’60s led, inevitably, to gratuitous violence. “The tension broke that day,” Didion wrote of the morning the crimes hit the news. “The paranoia was fulfilled.”

Cohen’s “The Future” takes place in a similarly entropic world. The speaker describes a hippie bacchanal, with “all the lousy little poets coming around, trying to sound like Charlie Manson.” The reference feels significant. The ’60s counterculture was supposed to tear down the heroes of the past—the benighted saints, kings, and soldiers—and replace them with better heroes. But who did it really give us? Charles Manson, a scraggly degenerate. Who killed people for no reason. And wrote bad poetry. “I’ve seen the future, brother,” Cohen sings. “It is murder.”

Once you become aware of the reactionary side to Cohen, you start seeing it everywhere, certainly in the spate of recent books about him—a corpus that hasn’t stopped growing since Cohen’s death eight years ago. (The obsession continues. Up next is a miniseries, So Long, Marianne, slated for release this year and featuring Hereditary star Alex Wolff.) In the final instalment (2022) of the Untold Stories trilogy, an oral history of Cohen’s life, journalist Michael Posner reveals that Cohen was a card-carrying member of the National Rifle Association and that, in his later days, he practised Zen Buddhism with a degree of rigidity and asceticism that his orthodox Jewish ancestors would surely relate to. (Despite eventually being ordained a Buddhist monk, Cohen never renounced Judaism. Promiscuous in his devotions, he dabbled in Christianity and Scientology too.)

A new academic essay collection, The Contemporary Leonard Cohen (2023), features a piece by the scholar Brian Trehearne about Cohen’s early poems. Trehearne notes that while we tend to associate Cohen’s writing with sensuality, he sometimes depicted cruelty and emotional numbness too. The poems that Trehearne cites feature horrific violence, described with an eerie sense of emotional detachment. “My lady was found mutilated / in a Mountain Street boarding house,” the speaker declares matter-of-factly in “Ballad,” from 1956. Does the speaker go on to express horror? Sadness? Shock? Not at all. He contemplates the beauty of his slain lover’s body, “her blouse / ripped away by anonymous hands.”

Cohen’s early writings are full of creeps like this guy. His first novel, A Ballet of Lepers, completed in 1961 but unpublished until 2022, depicts a rootless Montrealer who gets a visit from his estranged grandfather. At the train station, the grandfather beats a policeman. “I remember noting the agility and grace with which my grandfather accomplished the assault,” the narrator says. The act awakens a sense of cruelty within the narrator: he begins stalking and tormenting a baggage clerk from the station, and both grandfather and grandson together brutalize the narrator’s girlfriend. The crimes are motiveless but enacted with glee (which may itself be a kind of motive).

Trehearne doesn’t comment on A Ballet of Lepers specifically, but he seeks to explain Cohen’s fascination with mindless brutality, which he attributes to the legacy of the Holocaust (Does morality mean anything in a post-Auschwitz world?) and to a general aesthetic desire, among modernist writers, to reject sentimentality in favour of grim, dispassionate realism.

But conservatism is clearly at play here too. Cohen’s early characters are often emotionally stunted sadists living marginal lives in big, anonymous cities. Modernity has betrayed them. In the past, they might have had communities, traditions, and a shared set of ethical responsibilities; now they just have their impulses and appetites, unchecked by collective norms. There’s little remorse in A Ballet of Lepers, only boredom, a feeling that is palliated with ever-more-lurid violence.

And the antidote to this modern malaise? The writings of the ancients, of course. Cohen drew heavily from sacred and scriptural texts—the Torah, the Gospels, the proverbs of the Buddha, the Song of Solomon. But he wasn’t just name-checking his sources; he was mining them for wisdom. “Story of Isaac,” from his sophomore album, Songs from a Room, is a retelling of the most anguished Old Testament tale—the one in which God, as a loyalty test, instructs Abraham to butcher his son, and Abraham nearly complies—but it’s also a warning about the human instinct toward thoughtless violence.

Scepticism of modernity, anxieties about moral decay, fascination with the Biblical past—these are classically conservative themes, and they come up repeatedly in Cohen’s work. They’re not the only themes, of course. The point here isn’t to rebrand Cohen as some kind of crypto-reactionary but rather to acknowledge that his liberalism was muddied—or, if you prefer, enriched—by competing impulses.

If there is a plausible heir to Cohen’s musical legacy—the darkness, the nostalgia, the sensuality—it’s not the more straightforwardly political singer-songwriters today, like Jason Isbell, Margo Price, or Natalie Maines, performers who bemoan American militarism, critique toxic masculinity, denounce white privilege, and maintain a generally uncomplicated relationship with the progressive pieties of the moment. Rather, it’s the sad-girl balladeer Lana Del Rey, the pen name of singer-songwriter Elizabeth Grant.

In a surprising essay on Del Rey, Ben Woodfinden—a writer and academic who now manages communications for Conservative Party leader Pierre Poilievre—acknowledges that, in key respects, the artist embodies post-’60s liberated femininity: she sings about heroin fixes and fast cars and compulsive hookups in tawdry motels. But, Woodfinden notes, her songs are suffused with a sense of melancholy. Del Rey seems fearful that the pleasures of a hedonistic lifestyle may turn out to be as thin as rolling paper and as fleeting as a cocaine high. At times, she longs to retreat into nostalgia, a world of tract houses and chapel weddings, where the men are strong and silent and loyal to their wives.

Conservative fans—like the young reactionaries who worship Del Rey or the National Review critics who write breathlessly about Cohen—have picked up on themes that liberal audiences sometimes ignore. But everybody should pay attention to them. For progressives who occasionally, perhaps secretly, maintain conservative sympathies, performers like Cohen offer a safe way in. They invite you to explore contradictory ideas without abandoning your primary political loyalties. Cohen’s songs are mansions with many rooms. You can wander endlessly around them without leaving the property.

And if his liberalism often appears at odds with his reactionism, this isn’t always the case. The most thrilling moments in Cohen’s career are those in which the contradictions are somehow reconciled. When Cohen was in Israel, proximity to combat revitalized him. But in much of his work, it isn’t war that restores people’s spirits; it’s sex, that beloved, fraught, endlessly mutable human activity. And when Cohen wrote about sex (which he did most of the time), his humanistic and conservative impulses often aligned.

Cohen’s peers in the ’60s counterculture—the generation that staged bed-ins and chanted “Make Love Not War”—envisioned sex as a form of rebellion, a way of rejecting militarism, family values, and the prim norms of the postwar era. But for Cohen, sex is more ritualistic than revolutionary. In his best songs, the language of sex is also the language of sacrament and worship; narratives of lust and longing are intertwined with scenes from scripture. “Hallelujah” presents the Biblical story of the adulterous affair between King David and the soldier’s wife Bathsheba as a parable about human feebleness in the face of desire—a higher power to which all of us, even kings, must surrender. “Suzanne” describes, in the first verse, a lover’s obsession with his partner and, in the second, the devotion that early disciples bestowed upon Jesus.

In Cohen’s work, erotic and religious passions seem to spring from the same source. Try sex, Cohen is saying. It’s the hot new thing, invented in the ’60s and as old as creation. His lyric invites us to escape modernity—with its televised distractions and cheap consumables—and to commune with our ancient, corporeal selves.